Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Reasons behind "Order-of-Multiplication" Disputes

- 2.1 6 Reasons for Correctness

- 2.2 6 Reasons for Incorrectness

- 2.3 My Opinions

- 3. Multiplicative Circumstances

- 3.1 Multiplier-First Word Problems

- 3.2 Between "a x b" and "b x a"

- 3.3 "Multiple" and "Product" Multiplications

- 4. Characteristics of Japanese Math Education

- 5. Conclusion

- References

Please get access to https://github.com/takehiko/oomdoc for the links to related pages and the files under version control.

1. Introduction

Multiplication is the most important topic that Japanese elementary school pupils in the second grade learn. They write expressions using a times sign and recite the multiplication table called kuku. At present they tackle with the calculation of "4 x 12" which is beyond kuku, without computation on paper. For example, they draw "4 x 9 = 36" from the table of 4s, and have "4 x 10 = 40", "4 x 11 = 44", and "4 x 12 = 48" with the aid of the fact that the product increases by the size of the multiplicand when the multiplier increases by 1 [Isoda 2010]. Another solution is to lay out "4 x 12 = 12 x 4 = 12 + 12 + 12 + 12 = 48" using the commutative law and the repeated addition.

After that, the pupils solve word problems in a special form. For example:

"There are 5 dishes. 3 apples are on each dish. How many apples do you have altogether?" is the problem statement. There is attached an answer column for the numerical expression and the conclusive quantity. The pupil wrote in "5 x 3 = 15" and "15 apples". And then the sheet was red-penciled so that the total number might be right but the sentence wrong; the correct expression is "3 x 5 = 15". A basic idea of the "order of multiplication" is that they have to write "3 x 5" by turning over the two numbers to gain the correct answer, on the grounds of the "meaning of multiplication" that they learned.

The instruction of multiplication like this has been controversial, which is called a "order-of-multiplication" dispute. The critics raise concern about the way of teaching that "3 x 5" is one and only one correct answer to the above apple problem and claim opposition to teacher's putting a cross in a red pen on "5 x 3". The book focusing on this topic was published in 2011 [Takahashi 2011]. In October 2013, a debate was sparked up in a Korean forum [Link 2K] where a few comments linked to a blog article that I wrote two years ago. I am a stranger to Korean language, though, this was an opportunity to think of the perspectives on multiplication and the past achievements of it across the world.

The purpose of this document is to put principal opinions around the order-of-multiplication dispute in place. I will release it in Japanese, English, and Korean languages so that the readers outside Japan who are interested in this topic can understand an aspect of Japanese math education. As discussed later, I am in sympathy with the incorrectness described above under certain conditions.

Before the subject, I introduce a couple of educational circumstances of Japan. A multiplicative formula is denoted by "multiplicand x multiplier". A circle and a cross are marked in a red pen to indicate the correct and the incorrect answers respectively. A school year starts with April and ends with March in the following year.

2.1 6 Reasons for Correctness

Here I am posting a list of the dominant reasons why "5 x 3" should be a correct answer to the apple problem as well, based on copious amount of Internet resources (Web pages, blogs, forums, tweets, ...) and documents in print.

- A-1. Two factors are commutative. By the commutative law of multiplication, 5 x 3 = 3 x 5 holds.

- A-2. A "dealing-out" operation can swap the roles of multiplicand and multiplier; we can write "5 apples/round x 3 rounds = 15 apples".

- A-3. We can write "5 x 3" by arranging the apples in a rectangle shape.

- A-4. We can recognize the number of dishes as the multiplicand (or the basic quantity) and the number of apples per dish as the multiplier.

- A-5. With counters attached, "5 x 3 apples" and "3 apples x 5" are equivalent, and so are "5 dishes x 3 apples/dish" and "3 apples/dish x 5 dishes".

- A-6. In other countries, they write the multiplicand and the multiplier oppositely or do not think that the order matters.

I am showing how a "dealing-out" operation works to gain "5 x 3 = 15" using an animated GIF picture.

Two reasons labeled by A-2 and A-4 both make a point that 5 x 3 is correct under the assumption that a multiplicative expression is written as "multiplicand x multiplier". In contrast, A-5 and A-6 state that "multiplier x multiplicand" is also a valid mathematical formula.

If you would like to learn details of "counters" found in A-5, get access to [Link 5E]. In addition, the compound counters using "/" (per) emerged around 1970, so long as I read the books written by The Association of Mathematical Instruction (Sugaku Kyoiku Kyogikai) which promotes the style [Toyama 1961][Toyama 1971]. It is true that no such expressions are not seen in Japanese math textbooks, but the notion of counters is not unique to Japan. The concept of "referent" analyzed by Schwartz [Schwartz 1988] is similar to that.

2.2 6 Reasons for Incorrectness

The following list enumerates the principal reasons for the wrong answer.

- B-1. In this case, the number of apples per dish is the multiplicand while the number of dishes is the multiplier.

- B-2. "5 x 3" and "3 x 5" differ in meaning, although the products are the same.

- B-3. "5 x 3 = 15" shows the opposite situation regarding the numbers of apples and dishes.

- B-4. "5 x 3 = 15" leads to 15 dishes but not apples.

- B-5. With counters attached, "5 apples x 3" and "3 apples x 5" are different, and so are "5 apples/dish x 3 dishes" and "3 apples/dish x 5 dishes".

- B-6. Writing expressions in consideration of language and cultural differences is educationally valuable.

Here is an illustration of a lesson that involves B-3 and B-4 [Tsukubafuzoku 2003].

"There are 5 cars. How many tires do you have altogether?" is the word problem which is presented first. Sharing a tip that each car has 4 tires, the pupils are expected to write "4 x 5 = 20." If someone wrote "5 x 4", then the expression would represent "4 five-wheeled vehicles" or "4 houses each of which has 5 cars". They can understand visually that either situation is not what is shown in the original problem.

2.3 My Opinions

By using the two lists of reasons for correctness and incorrectness, we can discriminate various opinions seen in the order-of-multiplication dispute. As a matter of fact, I disagree with all of A-1 to A-6. First of all, the choice of operation which lets a solver select multiplication for a given word problem should precede the application of the commutative law mentioned in A-1.

The diversity of explanations for "5 x 3" should be considered not only using the dealing-out associated with A-2 but with interpretations indicated by B-3 and B-4. On the other hand, "3 x 5" will not cause misunderstanding, based on what they have ever learned about the meaning of multiplication. That is why I propose that children should select the less misconstrued expression between "a x b" and "b x a." Actually the comparison like this has been practiced in class before I took an interest in the advocacy, except that the expression with two factors exchanged is not interpreted with A-2.

For that matter, the dealing-out is established as an operation for partitive division [Anghileri 1988][Mitobe 2012]. We cannot afford to ignore the fact that the whole sum should be fixed in advance of the distribution manipulation whether or not the distributor knows the accurate count. On the other hand, the whole sum using multiplication is required in the setting like the apple problem but the way of distribution does not matter. See [MESSC 1986] for the relationship between distribution manipulations and four operations. A lesson study proposed in [Maekawa 2011] deals with the sum of oranges and is designed with the dealing-out in mind. However the plan dismisses the reason A-2 by noting that the teacher should let the pupils focus on the distributed result but not on how to hand out the objects, to determine the number of equal groups which is associated with the multiplicand.

A-3 is an approach to resolving a "multiple" problem using "product". Although The School Mathematics Study Group (SMSG) proposed this modeling in 1960s [Anghileri 1988], the society and the approach fell into a decline together with so-called New Math. I have never seen any lesson examples in Japan or children's understanding backed up by academic research [Nakajima 1968a][Mulligan 1992].

The reason A-4 is a sort of simple idea, and it has foundation in math education research [Vergnaud 1983][Vergnaud 1988]. However [Vergnaud 1988] also notes the difficulty in this recognition. Concurrently with a practice in 1950s [Nakano 1957] and with mathematical relations described in Elementary School Teaching Guide, it is good for the pupils in 4th or 5th grade to learn the way of viewing.

We have two conflicts in the lists: between A-5 and B-5, and between A-6 and B-6. The case with B-6 is not limited to Japan; according to the blog article by a Korean resident officer living in Belgium [Link 8K], he found a zero on his child's paper and told the young one to write a Western-style multiplicative expression after knowing "4 objects each in 5 bags", because they would not reside permanently. As the result of comparing books [Kobayashi 2012][Sato 2010][Schuberth 1995][Nakajima 1968b][Mori 2009][Moriya 2011], I give a decision in favor of B-5 and B-6 because those reasons bring the class where the learners select an expression from two or more ones by comparison.

Just the same, I would not approve of all the reasons B-1 to B-6. I agree with the first two reasons under the condition that the apple problem and others are on the test after the pupils learn B-1 and B-2 properly in class. The condition seems to be met on the grounds of lesson plans developed by teachers as well as textbooks which are well-organized. A book of educational evaluation [Tanaka 2008] also indicates a need for the discrimination between so-called a "per" quantity and a multiple.

It is likely that skeptics merge B-3 and B-4 to decrease the number of reasons for incorrectness. But those interpretations seem attractive separately while there are practical examples of instruction using the respective reasons. Asahi Shimbun offered the class by the newspaper article in 2011 where "2 x 8" would mean 2-arm octopuses [Link 9J], which is related to B-3. A lesson proposed in [Isoda 2013] also has relevance. I will show you another example of B-4 later.

As far as B-5 is concerned, it is necessary to compare "5 apples x 3 dishes" with "3 apples x 5 dishes", I suppose. Vergnaud [Vergnaud 1983] pointed out that it is not clear why "4 cakes x 15 cents" yields cents and not cakes, just before explaining multiplicative structures using 2 x 2 tables, and I also suppose that his problem consciousness is directed to Japanese society where the quantities of goods are often specified as "5 pieces x 3 packs" or "1.5 kg x 4 boxes". By the way I have seen "3 x 80g" and "75g x 5" outside Japan, and we can find the heuristic rule from here that neither a physical unit nor a counter is attached to the multiplier.

Finally, I would like to comment on B-6; culture should include the history in a country. I hope that children understand various ways of describing math expressions which differ from country to country and from age to age, and that they offer an answer to the problem at hand.

3.1 Multiplier-First Word Problems

The apple problem is intended to let pupils write "multiplicand x multiplier" for a word problem where the multiplier appears first and then the multiplicand is described. We refer to a problem in this form as a "multiplier-first" word problem. Multiplier-first word problems have a history for several decades.

To the best of my knowledge, the oldest example is found in the prototype of Elementary School Teaching Guide for the Japanese Course of Study, Mathematics, published in 1951 [Link 10J]. It is reported that more than a few pupils replied the incorrect expression in calculating the number of pencils using multiplication, where the writer inferred from their reactions that they lined the two numbers up and sandwiched in the times sign without thinking deeply, and that they were incapable of organizing the situation for a valid choice of operation. The teacher told the pupils that the expression did not fit in with the problem because it would yield the number of persons. Here B-4 was adopted.

In a society, the newspaper article of Asahi Shimbun in 1971 [Link 11J] has an important implication. "There are 6 children and we will give 4 oranges to each child. How many oranges do you have altogether?" was on the test at an elementary school. When knowing that "6 x 4" was incorrect, a father referred to the school, the local education committee, and the Ministry of Education. Hiraku Toyama, who was a mathematician and a person with influence in a postwar math education of Japan, contributed an article to Kagaku Asahi in the same year [Toyama 1972]. He argued in this article that "6 x 4" should be also a right answer by using the dealing-out (A-2), the commutative law (A-1), and a rectangular arrangement of desks (A-3).

When we look at the history of Japanese math education, however, Toyama's opinion did not affected to the majority. Multiplier-first word problems has been used as teachers put weight on the meaning of multiplication. The questions can be seen in the books written by teachers or experts of math education, in scholarly research, and in surveys on academic performance. Among teachers, Hiroshi Kishimoto and Hiroshi Tanaka explained in their respective books [Kishimoto 2003][Tanaka 2009] that the children write the wrong multiplicative expression for multiplier-first word problems in nine cases out of ten.

According to the scholarly research by Shigehiro Kinda [Kinda 2008], about 20 percent of second-year pupils answered a "multiplier x multiplicand" expression to a multiplier-first word problem although they had already learned multiplication. Beyond that, about 60 percent of undergraduate students answered the same. Note that they gave a correct answer to the multiplicand-first one.

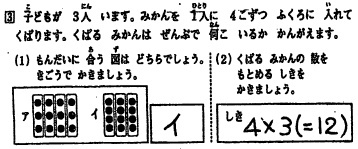

The Tokyo Arithmetic Educational Study Group (Tokyo-to Sansu Kyoiku Kenkyukai) conducted the surveys on academic performance regularly. In 2012 school year [Link 12J], pupils in the second grade dealt with the following multiplier-first word problem.

The problem statement begins with "There are 3 children. We will make bags with 4 oranges each to hand out. Let's think how many oranges we need." Pupils chose the appropriate one from two figures and wrote the expression. These two questions are intended to confirm the children's competence to recognize the mathematical relations rightly and to write a suitable multiplicative expression. In the result, 54 percent of answers were correct both in figure and in expression, 28 percent correct only in figure, and 6 percent correct only in expression, among about 60,000 respondents.

As seen above, multiplier-first word problems has been utilized for the assessment of the meaning of multiplication for a long time. The result has been, as a matter of course, used to give finely textured lessons. I have to note that multiplier-first word problems are frequently seen in early elementary grades while division word problems are popular in the upper grades. For example, pupils in the sixth grade answered to "An iron bar measures 8 m and weighs 4 kg. How much does the same iron bar of 1 m weigh?" in the nationwide survey on academic performance of Japan carried out in April 2010 [Link 13J]. A correct expression is not "8 ÷ 4" but "4 ÷ 8".

3.2 Between "a x b" and "b x a"

To realize differences between "a x b" and "b x a" is another way to understand the meaning of multiplication. We can see the examples from Japan and abroad.

First of all, look at a math textbook of Japan. A textbook published by Tokyo Shoseki in 2011 has a pair of word problems [Link 14J]: "You will give 2 pencils to each person, and there are 5 people. How many pencils do you have altogether?" and "There are 2 people, and you will give 5 pencils each. How many pencils do you have altogether?" Although the number 2 appears first and then 5 is indicated in both word problems, they describe the different situations. And the former corresponds to "2 x 5" and the latter to "5 x 2". Note that the word problem which begins with "There are 2 people" is multiplier-first; when pupils make a mistake in the apple problem, a teacher can let them, including the teacher, open the textbook to take another look at this problem. A textbook published by Dainippon Tosho also has a similar pair of multiplicative word problems [Link 15J].

In the rest of this section I would like to introduce the cases from the books in English. Anghileri and Johnson [Anghileri 1988] explain the difference between "three fours" and "four threes" by using the real life situation where 3 children each having 4 candies are luckier than 4 children each having 3 candies. They also said that whereas the commutative law is a property of numbers, "3 x 4" may not be the same as "4 x 3" in real life. Those ideas are associated with B-2 and B-5.

Vergnaud and Greer separately pointed out the difference between the multiplication of pure numbers and that used in elementary school arithmetic. I already picked up "4 cakes x 15 cents" with regard to Vergnaud [Vergnaud 1983], and he noted just before that a child multiplies 4×15 or 15×4 to find the answer. Greer [Greer 1992] presented with the fact that "A rocket travels at a speed of 16 miles per second. How far does it travel in 0.85 seconds?" is difficult for children because they are apt to choose "16 ÷ 0.85", although they can make out the multiplication correctly for the word problem with the two numbers swapped. This is a multiplier effect, that is, the difficulty of recognizing multiplication as the appropriate operation for the solution of a problem depends on whether the multiplier is an integer, a decimal greater than 1, or a decimal less than 1, bud not on the multiplicand. A makeup examination of the multiplier effect was conducted in Japan [Ohara 2007].

Those who criticize the order-of-multiplication insist that the form "multiplicand x multiplier" is just a shortcut method for introducing the multiplication, and that "multiplier x multiplicand" is accepted after they learn the commutative law of multiplication [Takahashi 2011]. However that kind of pretense does not seem to account nicely for Vergnaud's real-life example and the observational features by Greer and others.

3.3 "Multiple" and "Product" Multiplications

Through a range of publications from Japan and abroad, we can learn a lot about multiplication classifications. It is useful to be aware of the separation between "multiple" and "product". In a "multiple" multiplication, the multiplicand and the result are the same in quantity while the multiplier is interpreted as a ratio or a magnification factor; even if the multiplier is some kind of a quantity, it is dimensionless in computation. On the other hand, a "product" multiplication includes the situation where two quantities produce another quantity in a multiplicative way, as well as pure numbers' multiplication. A detailed classification table can be read in [Greer 1992] although it employs the bisection. If you would like to trisect the meaning of multiplication, you may know "scholar relationship", "proportional function", and "multiple proportion" presented by Tsuyoshi Mori [Mori 1973] and Vergnaud [Vergnaud 1983]. For one more push, "repeated addition" is the fourth meaning as set forth in [Tanaka 2008].

I would like to tell you how to identify the multiplication sort readily. Assume that "a x b = p" represents a situation. If a, b, and p are the same in quantity or p is not similar to a or b, then it is a "product" multiplication; a and b are the factors but it is meaningless to distinguish the multiplicand and the multiplier between them. By contrast, if p is the same in quantity as either one of the two, then it is a "multiple" multiplication; the similar one of a and b is the multiplicand and the other is the multiplier. "4 cakes x 15 cents" is a sort of "multiple" while calculating area or volume by means of length x width or area of base x height is associated with "product".

Let us share an example that demonstrates the combination of "multiple" and "product". When 10-cent coins are arranged in the following 3 x 4 rectangular shape, how much money do you have altogether?

Lengthwise counting leads to 40 cents while you can find 30 cents in the cross direction. But we must not compute the amount by means of the product of the two sums, i.e., 30 x 40 = 1200. In reality we have just 120 cents. 12 coins are on the table, and the expression for the situation is 3 x 4 = 12 (you may write 4 x 3 = 12). Then the amount can be correctly calculated by 10 x 12 = 120. These two multiplicative expressions can be unified to the new one namely 10 x 3 x 4 = 120. When the left-hand side is worked out as (10 x 3) x 4 = 30 x 4 = 120, this computation relates the fact that there are 4 columns of 30 cents each. In addition, we are able to find the associative law of multiplication.

If all the 10-cent coins are replaced with marbles, then the figure is listed on Elementary School Teaching Guide. Both "3 x 4" and "4 x 3" are accepted there because the situation belongs to "product" or Cartesian product. In the meantime, word problems in dispute including the apple problem are closely related to "multiple". When reading Toyama's article [Toyama 1972] in consideration of the bisection, we can understand that the notions of "multiple" and "product" were unspecific in it. He delivered his perception change of multiplicative models and instruction methods in 1979 [Toyama 1979], half a year before he died.

4. Characteristics of Japanese Math Education

I clarify the characteristics of Japanese math education with supplementary statements.

The biggest feature is how a class is conducted. It is regarded as a good lesson among school teachers that after the teacher sets a goal of the lesson, the pupils put effort into one or small number of problems within 45 minutes in the classroom. They do not only write expressions and answers but may make a verbal response of why they get to the answer. In addition, teachers take count of the diversity of the pupils' responses to a central problem in the class [Soma 2011]. This way of classroom management was highlighted over the world since the book entitled "The Teaching Gap" [Stigler 1999] was put out which includes the international classroom comparison among U.S., Germany, and Japan. Teachers commonly prepare "lesson plans" in advance of the lesson [Tsukubafuzoku 2003][Isoda 2007][Maekawa 2011][Takahashi A. 2011], while it is an erroneous view that a teacher carry out lessons along the textbook or automatically complying with the guidance book in existence. Although you are not a teacher, you can find on the net PDF and/or Microsoft Word documents of lesson plans. About the multiplication in the second grade, there are many lesson plans that are involved with B-1 and B-2.

Japan is a developed country and an exporting nation of education [Link 16J]. For example, the math textbooks by Tokyo Shoseki and Keirinkan were translated into English for sale [Link 17J][Yoshida 2009][Link 18J][Link 19J]. They are used by teachers and researchers who are concerned with Japanese math education, and by Japanese pupils who live abroad today and will fly back home in the future.

Exportation of educational contents and instruction methods, however, does not mean that the trading countries should follow Japanese form. Actually there are found cases with the consideration of the language and culture of local countries. For instance, Takuya Baba [Baba 2002] presented words of caution for the curriculum developments over global cooperation on education, by showing the cognitive load through the fact that the word order of multiplication in Thai is the same as in Japanese while the multiplicative expressions were in reverse due to the textbooks affected by Western style. Also, guidance books written in Spanish were published in a joint project by University of Tsukuba in Japan and Department of Education in Mexico [Isoda 2009]. In the theoretical framework, the symbol "x" with the letter "j" by a subscript denotes the times sign in Japanese, with a sensitivity to the multiplicative expressions in Spanish and in Japanese.

Let's get back to talking about the situation in Japan. The multiplicative expression in the form "multiplicand x multiplier" is common knowledge. Apart from size or financial indications, we Japanese recognize the quantities facing this form in our daily life, although the product is not specified. For the cake problem that Vergnaud pointed out, we usually write "150 yen x 4 pieces" for example (a 150-yen cake is a bit cheap on a personal note). In Japanese, "a x b" reads "a ga b" in a natural way. Sometimes "a" is not quantitative; in a video game [Link 20J], a coffin with "x2" on the bottom right corner represents the situation where the party has 2 dead bodies which are expected to return to life.

Surveys on academic performance has an interesting property. Unlike usual tests and entrance exams, each answer paper is not graded in general. The executants are concerned with answer patterns and reaction rates rather than pupils' marks. In other words, such a survey is carried out not for either finding brilliant persons or picking dropouts, but for perceiving collective scholastic abilities to improve education contents. Questions are released subsequently in principle. In the recent nationwide surveys on academic performance of Japan, National Institute for Educational Policy Research unveils the questions and answers just after the test is over, and several months after, the institute makes public bulletin reports which includes the comments based on the answer patterns with response rates ([Link 21J] for 2013).

The order of multiplication does not matter in the nationwide surveys because the flash reports and detailed documentations add a statement, in the tables of answer patterns, which notes that expressions where a multiplier and a multiplicand are exchanged are allowed. In contrast, the surveys in Tokyo-to have regarded "multiplier x multiplicand" expressions as incorrect answers to a word problem including fractions, for the sixth graders. Also in other surveys and textbooks, multiplicand-first word problems are provided and if a pupil turns over two numbers and writes "multiplier x multiplicand" expression, then the teacher or the grader decides that the pupil cannot understand the meaning of multiplication.

5. Conclusion

I have shown two ideas around the "order-of-multiplication" dispute. In the first half of this document, after sketching out for understanding the dispute, I proposed two lists of 6 reasons each for correctness and incorrectness. The reasons are made short and somewhat indistinct, so that each item can be related in and out of the list, such as the combination of A-2, B-3, and A-4 for interpretation. By examining an opinions on the net or in print with these lists, we can easily understand what reason the sender approves of and what he or she refuses.

The last half dealt with cases of questions associated with the dispute and seen in Japan and other countries. Although it was made up for the purpose of the international understanding of multiplication and math education, the examples in this document are a tiny fraction of the experiences accumulated in math education. For example, theories of quantities written by mathematicians mainly in 1970s [Kojima 1976][Nagumo 1977][Tamura 1978] would be useful as the basis of math education at present. If you are interested in country-level scholastic abilities, I recommend Elementary School Teaching Guide of Japan [URL 1] (English version is available [Isoda 2010]) and Common Core State Standards for Mathematics in U.S [Link 22E].

Future works include another kind of arrangement of literature which supports the "order-of-multiplication" dispute, such as the relationship between math education and mathematics, and educational environments from home and abroad.

References

- [Isoda 2010] Isoda, M. (Ed.): Elementary School Teaching Guide for the Japanese Course of Study: Mathematics (Grade 1-6), 2010. http://www.globaledresources.com/products/assets/Teaching%20Guide%20Elementary.pdf

- [Takahashi 2011] 高橋誠: かけ算には順序があるのか, 岩波科学ライブラリー180, 岩波書店 (2011). isbn:9784000295802

- [Schwartz 1988] Schwartz, J. L.: "Intensive quantity and referent transforming arithmetic operations", Number concepts and operations in the middle grades, National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. pp.41-52 (1988). isbn:0873532651

- [Tsukubafuzoku 2003] 筑波大学附属小学校算数部(編集): 板書で見る全単元・全時間の授業の すべて 小学校算数2年下, 東洋館出版社 (2003). isbn:9784491019376

- [Anghileri 1988] Anghileri, J. and Johnson, D. C.: "Arithmetic Operations on Whole Numbers: Multiplication and Division", Teaching Mathematics in Grades K-8, Longman Higher Education, pp.146-189 (1988). isbn:0205110762

- [Mitobe 2012] 水戸部修治, 笠井健一, 村山哲哉, 杉田洋, 直山木綿子, 澤井陽介: 教科調査官が語るこれからの授業 小学校―言語活動を生かし「思考力・判断力・表現力」を育む授業とは, 図書文化社 (2012). isbn:9784810026160

- [MESSC 1986] 文部省: 数と計算の指導―小学校算数指導資料, 大日本図書 (1986). isbn:4477181655

- [Maekawa 2011] 前川公一, 志水廣: 365日の算数学習指導案 1・2年編, 明治図書出版 (2011). isbn:9784180808335

- [Nakajima 1968a] 中島健三: 乗法の意味の指導について, 日本数学教育会誌, Vol.50, No.2, pp.2-6 (1968). http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/110003849500

- [Mulligan 1992] Mulligan, J.: "Children's Solutions to Multiplication and Division Word Problems: A Longitudinal Study", Mathematics Education Research Journal, Vol.4, No.1, pp.24-41 (1992). http://www.merga.net.au/documents/MERJ_4_1_Mulligan.pdf

- [Vergnaud 1983] Vergnaud, G.: "Multiplicative Structures", Acquisition of mathematics concepts and processes, Academic Press, pp.127-174 (1983). isbn:012444220X

- [Vergnaud 1988] Vergnaud, G.: "Multiplicative Structures", Number Concepts and Operations in the Middle Grades, Vol.2, pp.141-161 (1988). isbn:0873532651

- [Nakano 1957] 中野佐三(編): 算数科の教育心理, 児童心理選書 第八巻, 金子書房 (1957). asin:B000JBN9M6

- [Kobayashi 2012] 小林道正: 数とは何か?, ベレ出版 (2012). isbn:9784860643409

- [Sato 2010] 佐藤俊太郎(編著): 算数・数学教育つれづれ草, 東洋館出版社 (2010). isbn:9784491026183

- [Schuberth 1995] Schuberth, E.(著), 森章吾(訳): シュタイナー学校の算数の時間, 水声社 (1995). isbn:4891763159

- [Nakajima 1968b] 中島健三: 乗法の意味についての論争と問題点についての考察, 日本数学教育会誌, Vol.50, No.6, pp.74-77 (1968). http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/110003849391

- [Mori 2009] 森毅: 数の現象学, 筑摩書房 (2009). isbn:9784480091963

- [Moriya 2011] 守屋誠司: 小学校指導法 算数, 玉川大学出版部 (2011). isbn:9784472404221

- [Toyama 1961] 遠山啓(編): 算数に強くなる水道方式入門, 国土社 (1961). asin:B000JALYQ0

- [Toyama 1971] 遠山啓, 銀林浩(編): 新版 水道方式入門 整数編, 国土社 (1971). isbn:4337478094

- [Tanaka 2008] 田中耕治: 教育評価, 岩波書店 (2008). isbn:9784000280501

- [Isoda 2013] 礒田正美(監修), 田中秀典, 末原久史(編著): アイディアシートでうまくいく! 算数科問題解決授業スタンダード, 明治図書出版 (2013). isbn:9784180047208

- [Toyama 1972] 遠山啓: 6×4,4×6論争にひそむ意味, 科学朝日1972年5月号, 朝日新聞社. [Toyama 1978] pp.114-121.

- [Toyama 1978] 遠山啓: 量とはなにか I, 遠山啓著作集数学教育論シリーズ, Vol.5 (1978). asin:B000J8MZYC

- [Kishimoto 2003] 岸本裕史: どの子も伸びる算数力, 小学館 (2003). isbn:4093874603

- [Tanaka 2009] 田中博史: 田中博史の算数授業のつくり方, 東洋館出版社 (2009). isbn:9784491023984

- [Kinda 2008] 金田茂裕: 小学2年生の乗法場面に関する理解, 東洋大学文学部紀要 教育学科編, No.34, pp.39-47 (2008). http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/40016569351

- [Greer 1992] Greer, B.: "Multiplication and Division as Models of Situations, Handbook of Research on Mathematics Teaching and Learning", National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, pp.276-295 (1992). isbn:1593115989

- [Ohara 2007] 小原豊: 小学校児童による有理数の乗法における乗数効果の分析, 鳴門教育大学研究紀要, Vol.22, pp.206-215 (2007). http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/110006184927

- [Mori 1973] 森毅, 竹内啓: 数学の世界―それは現代人に何を意味するか, 中央公論新社 (1973). isbn:4121003179

- [Toyama 1979] 遠山啓: 内包量・外延量と微分積分 (1979). [Toyama 1981] pp.78-91.

- [Toyama 1981] 遠山啓: 量とはなにか II, 遠山啓著作集数学教育論シリーズ, Vol.6 (1981). asin:B000J7WQJW

- [Soma 2011] 相馬一彦, 早勢裕明: 算数科「問題解決の授業」に生きる「問題」集, 明治図書出版 (2011). isbn:9784180236275

- [Stigler 1999] Stigler, J. W. and Hiebert, J.: "The Teaching Gap: Best Ideas from the World's Teachers for Improving Education in the Classroom", Free Press (1999). isbn:0684852748

- [Yoshida 2009] Yoshida, M.: "Is Multiplication Just Repeated Addition? ― Insights from Japanese Mathematics Textbooks for Expanding the Multiplication Concept", 2009 NCTM Annual Conference (2009). http://www.globaledresources.com/resources/assets/042309_Multiplication_v2.pdf

- [Baba 2002] 馬場卓也: 数学教育協力における文化的な側面の基礎的研究,平成13年度 国際協力事業団 客員研究員報告書 (2002). http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA65639013 http://jica-ri.jica.go.jp/IFIC_and_JBICI-Studies/jica-ri/publication/archives/jica/kyakuin/pdf/200203_08.pdf

- [Isoda 2007] Isoda, M., Stephens, M., Ohara, Y. and Miyakawa, T. (Eds.): "Japanese Lesson Study in Mathematics: Its Impact, Diversity and Potential for Educational Improvement", World Scientific Publishing (2007). isbn:9789812705440

- [Takahashi A. 2011] 高橋昭彦: 算数数学科における学習指導の質を高める授業研究の特性とメカニズムに関する考察―アメリカにおける10年間の試行錯誤から学ぶこと―, 日本数学教育学会誌, Vol.93, No.12 (算数教育60-6), pp.2-9 (2011). http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/110008898076

- [Isoda 2009] Isoda, M. and Olfos, R.: "La enseñanza de la multiplicación: el estudio de clases y las demandas curriculares", Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso (2009). http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA89718362 http://math-info.criced.tsukuba.ac.jp/upload/MultiplicationIsodaOlfos.pdf

- [Kojima 1976] 小島順: 線型代数, 日本放送出版協会 (1976). asin:B000JA0OCK

- [Nagumo 1977] Nagumo, M.: Quantities and real numbers, Osaka Journal of Mathematics, Vol.14, Num.1, pp.1-10 (1977). http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.ojm/1200770204

- [Tamura 1978] 田村二郎: 量と数の理論, 日本評論社 (1978). asin:B000J8KINM

- [Link 1J] http://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/new-cs/youryou/syokaisetsu/

- [Link 2K] http://www.todayhumor.co.kr/board/view.php?table=humordata&no=1454118

- [Link 3Et] http://d.hatena.ne.jp/takehikom/20111224/1324659582

- [Link 4J] http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%8A%A9%E6%95%B0%E8%A9%9E

- [Link 5E] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_counter_word

- [Link 6Jt] http://d.hatena.ne.jp/takehikom/20120125/1327442079

- [Link 7Et] http://d.hatena.ne.jp/takehikom/20120612/1339436326

- [Link 8K] http://cafe.daum.net/seaugjang/9MER/23

- [Link 9J] http://www.asahi.com/edu/student/teacher/TKY201101160133.html

- [Link 10J] http://www.nier.go.jp/guideline/s26em/chap5.htm

- [Link 11J] http://ameblo.jp/metameta7/entry-10196970407.html

- [Link 12J] http://tosanken.main.jp/data/H25/happyou/20131018-7.pdf

- [Link 13J] http://www.nier.go.jp/10chousa/10chousa.htm

- [Link 14J] http://ten.tokyo-shoseki.co.jp/text/shou/subject/sansu/tsumazuki/ebook/pdf/2.pdf

- [Link 15J] http://www.dainippon-tosho.co.jp/sho/sansuu/text/index.html

- [Link 16J] http://www.jica.go.jp/activities/issues/education/index.html

- [Link 17J] http://shop.tokyo-shoseki.co.jp/shopap/feature/theme0053/

- [Link 18J] http://keirin.shop29.makeshop.jp/shopbrand/003/O/

- [Link 19J] http://www.shinko-keirin.co.jp/keirinkan/pr/risukeirin/pdf/no001_11.pdf

- [Link 20J] http://www.dqmp.jp/

- [Link 21J] http://www.nier.go.jp/13chousa/13chousa.htm

- [Link 22E] http://www.corestandards.org/assets/CCSSI_Math%20Standards.pdf

(Last updated: Sat Apr 05 21:12:41 JST 2014; Released: Fri Nov 15 21:57:45 JST 2013)