目次

- Davies (1841)

- Nagumo (1977)

- Freudenthal (1983)

- Vergnaud (1983)

- Anghileri&Johnson (1988)

- Vergnaud (1988)

- Greer (1992)

- Shoenfield (2008)

- Yoshida (2009)

- Isoda&Olfos (2009)

- Nunokawa (2010)

- Vorderman (2010)

Davies (1841)

- Davies, C. (1841). Arithmetic: Designed for Academies and Schools, A.S. Barners. http://books.google.co.jp/books?id=bCSHpZu-OMQC

Multiplication is a short method of repeating one number as many times as there are units in another.

The number to be repeated is called the multiplicand.

The number denoting how many times the multiplicand is to be repeated, is called the multiplier.

The number arising from repeating the multiplicand as many times as there are units in the multiplier, is called the product.

The multiplicand and multiplier are called factors, or producers of the product.

The sign ×, placed between two numbers, denotes that they are to be multiplied together. It is called, the sign of multiplication.

(かけ算は,一つの数を,もう一つの数の数だけ繰り返すことの簡潔な方法である.

繰り返される数のことを,かけられる数という.

かけられる数が何回繰り返されるかを表した数を,かける数という.

かけられる数を,かける数の回数だけ繰り返すことで生じる数は,積という.

かけられる数とかける数は因数,あるいは積を生成するものと呼ばれる.

記号×は,2つの数の間に置かれ,それらをかけ合わせることを表す.これは乗算記号と呼ばれる.)

(p.42)

Nagumo (1977)

- Nagumo, M. (1977). Quantities and real numbers, Osaka Journal of Mathematics, Vol.14, No.1, pp.1-10. http://projecteuclid.org/DPubS?verb=Display&version=1.0&service=UI&handle=euclid.ojm/1200770204&page=record

The contents of this note had been already published by the author in Japanese in a mimeographed copy "Zenkoku Shijo Sugaku Danwakai" (1944).

(このメモの内容は,日本語で書き,ガリ版刷りで「全国紙上数学談話会」(1944年)で公開したものである.)

(p.1)

上記の「1944」は誤記であり,正しくは「1942」です.

For any a∈Q and any natural number n (n∈N), we define na∈Q by induction: 1a=a and (n+1)a=na+a.

(ある量の集合Qに属する任意のaおよび任意の自然数nに対して,Qに属するnaを帰納法により定義する.1a=a,および(n+1)a=na+a.)

(p.2)

Freudenthal (1983)

- Freudenthal, H. (1983). Didactical Phenomenology of Mathematical Structures, Reidel. asin:9027722617

電子化されたものがhttp://books.google.co.jp/books?id=Ow3KrKYnZLwC&printsec=frontcover&hl=ja&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=falseより参照できますが,「61〜62ページはこのプレビューに表示されません。」と出ました(2013年2月9日).

☆

Vergnaud (1983)

- Vergnaud, G. (1983). Multiplicative Structures, In Lesh, R. and Landau, M. (Eds.), Acquisition of mathematics concepts and processes, Academic Press, pp.127-174. isbn:012444220X

Example 1. Richard buys 4 cakes priced at 15 cents each. How much does he have to pay?

a = 15, b = 4, M1 = [number of cakes], M2 = [costs]

(例1: リチャードは,1個15セントのケーキを4個買います.いくら払わないといけませんか?

a = 15, b = 4, M1 = [ケーキの個数], M2 = [金額])

(p.129)

From Schema 5.1 children can extract a×b=x. In Example 1, for instance, the child recognizes the situation to be multiplicative, and therefore multiplies 4×15 or 15×4 to find the answer. This binary composition is correct if a and b are viewed as numbers. But, if they are viewed as magnitudes, it is not clear why 4 cakes × 15 cents yields cents and not cakes.

(図5.1から,子どもたちはa×b=xを得る.たとえば例1では,子どもはかけ算の場面であることを認識し,その結果4×15か15×4のいずれかの式で表す.この2項演算は,aとbをともに(純粋な)数と見るなら正しい.しかし,(量の)大きさとして見たとき,4個×15セントによって60セントが得られ60個ではないのがなぜかというと,明らかではない.)

(p.129)

In Schema 5.3, ×a is a function operator because it represents the coefficient of the linear function from M1 to M2. Its dimension is the quotient of two other dimensions (e.g., cents per cake, kg per ha).

(図5.3において,「×a」は関数作用素である.というのもそれはM1からM2への比例関係の係数(比例定数)を表すからである.その次元は,2つの異なる次元の商となる(たとえば,「ケーキ1個あたりの単価(セント)」,「ヘクタールあたりのキログラム」).)

(p.130)

Another procedure for solving multiplication problem consists of adding a+a+a... (b times), but it is not a multiplicative procedure. It only shows that the scalar procedure relies upon iteration of addition. One does not find, in young children, the symmetric procedure b+b+b+... (a times) because it is not meaningful.

(乗法の問題を解く別の手続きは,a+a+a... によりaのb倍を求めることである.それは,累加に基づくスカラーの計算手続きにすぎない.この場合,低年齢の小児は,b+b+b+...によるbのa倍という対称的な式を得ることができない.)

(p.130)

The Cartesian product is so nice that it has very often been used (in France anyway) to introduce multiplication in the second and third grades of elementary school. But many children fail to understand multiplication when it is introduced this way. The arithmetical structure of the Cartesian product, as a product of measures, is indeed very difficult and cannot really be mastered until it is analyzed as a double proportion. Simple proportions should come first.

(デカルト積は,(積の考え方として)非常にいいので,フランスではとにかく,小学校の第2〜3学年でかけ算を導入する際に非常によく使われてきた.しかしこの方法で導入すると,多くの児童が,かけ算の理解に失敗している.量の積として,デカルト積による算術的(乗法的)な構造というのは実のところ非常に難しく,複比例として理解できるようになるまでは,その修得は困難である.単純な比例(割合)の問題を最初にもってくるべきである.)

(p.135)

"A farm, in the Beauce country, has an area of 254.5 ha. Half of it is devoted to growing wheat. The average crop is 6800 kg of wheat per ha. One needs 1.2 kg grain to make 1kg flour; 1.5 kg flour to make 4 loaves. One loaf is, on the average, the daily comsumption of two persons."

(「Beauceのある農場は,254.5ヘクタールの敷地を持つ.その半分で,小麦を栽培している.1ヘクタールあたり平均6800キログラムの収穫量がある.1キログラムの小麦粉を得るには,小麦1.2キログラムを必要とする.1.5キログラムの小麦粉があれば,パン4斤ができる.1斤は,平均して,2人の1日の消費量である.」)

(pp.169-170)

Anghileri & Johnson (1988)

- Anghileri, J. and Johnson, D.C. (1988). Arithmetic Operations on Whole Numbers: Multiplication and Division. In Post, T.R. (Ed.), Teaching Mathematics in Grades K-8, Longman Higher Education, Allyn and Bacon, pp.146-189. asin:0205110762

Research on the learning of multiplication and division, while somewhat diverse, has generally focused on four main areas---teaching methods, structure and properties, children's understanding of the operations, and children's use of the algorithms. Research by Fullerton (1955), Norman (1955), and Gunderson (1955) provide some useful results in the area of teaching methods (and these are reflected in the recommendations noted in later sections in this chapter).

Useful work in the area of structure and properties has been carried out by Schell (1964), Gray (1965), and Willington (1967). Of particular interest in this area are those studies that have shown that different models of the operations of multiplication and division vary in their relative difficulty. Zweng (1964) found that children can understand the "measurement" (repeated subtraction) concept of division more readily than the "partition" (sharing) concept. Hervey (1966) considered the responses made by second-grade children to multiplication problems based on "equal addends" concept and on the "Cartesian product" concept and found that the equal addends problems were significantly less difficult. Hervey noted that it was less difficult for the children to choose the way to think about the problem for this type. This result was corroborated by Brown (1981) whose work in the United Kingdom with older children (10 to 14 years of age) showed that "repeated addition" and "rate" models for multiplication were easier than "Cartesian product" models.

(乗法・除法の学習に関する研究には,さまざまな形が見られるものの,おおむね次の4つの領域が注目されている.「指導法」「構造および性質」「演算に対する理解」「計算手続きの利用」である.Fullerton (1955),Norman (1955),Gunderson (1955)による研究は,指導法に関して有用な結果を残している(あとの節で,推薦する文献として取り上げる).

構造および性質に関しては,Schell (1964),Gray (1965),Willington (1967)が価値のある成果を挙げている.それらの研究により,乗法・除法という演算のさまざまなモデルが,それぞれ異なった難しさを持っているのを示したことは,特に興味深い.Zweng (1964)は,児童らには「分割」(共有)の概念よりも,「測定」(累減)の概念のほうがよりよく理解できることを示した.Hervey (1966)は,2年生の児童らに「累加」と「直積」の概念に基づく出題を与え,その反応をもとに,累加の問題のほうが困難さが有意に低いことを示した.児童らがこの種の問題を考えるとき,そのやり方を選ぶのが比較的困難でないことを,Herveyは指摘している.この結果は,Brown (1981)によって裏付けられている.Brownは,イギリスで10〜14歳の子どもたちに対して調査し,「累加」や「割合」のモデルが「直積」のモデルよりも容易であることを示した.)

(p.151)

When considering how the symbolic expression 3×4 is interpreted by adults and children, we find the most common expressions are "3 multiplied by 4," "3 times 4," and "3 fours." Some people will use the expressions quite interchangeably on the understanding that all three are equivalent; in the domain of mathematics this may be acceptable but in real life there is an important distinction between these different interpretations. On one hand "3 times 4" and "3 fours" usually relate to three sets of four objects and are consistent with "3 lots of 4."

For children, three lots of four and four lots of three are fundamentally different. They think in concrete terms---three children each having four candies are luckier than four children each having three candies although the total number of candies is the same.

(3×4という式が何なのか,大人と子どもが説明すると,たいてい「3に4をかける」「3倍の4」「3つの4」のいずれかとなる.これら3つの解釈を同じものとして理解し,どれを使っても変わりがないように,3×4という式を使う人もいる.数学的には,その扱いで問題ないかもしれないが,日常生活においては,これらの解釈には大きな違いがある.「3倍の4」と「3つの4」は普通,4つのモノからなる集合が3つある状態に関連づけられ,「4が3つ」に対応する.

子どもたちにとって,「4が3つ」と「3が4つ」は基本的に別物である.具体物で考えると---4つずつキャンディを持っている3人の子どもは,3つずつキャンディを持っている4人の子どもよりも,運がいい.キャンディの総数は同じなのだけれども.)

(p.157)

Exercises

1. Give some real-life examples of situations in which a multiplication product a×b (for example, 5×6) is not the same as b×a (6×5).

(練習問題.1. a×bとb×a(例えば,5×6と6×5)が同じでないような,日常生活の例を挙げなさい.)

(p.158)

Allocation/Rate---Multiplication

This arises when there is a many-to-one matching in which equal sets (portions) are matched using a tally of objects (owners). The example in Fig. 6-12 shows three cats each with two fish.

At first, this may appear to be identical with the previous equal groupings. Note however the presence of a tally set, the cats, which in fact makes it easier. Young children find it easier to "give two candies to each doll" (three dolls) than to "make three equal portions of two candies". The language of matching is more familiar to them, and the presence of a tally set means that only one of the two numbers involved needs to be internalized and acted on.

(配分・割合のかけ算

これは,同じ数のひとまとまりが,対象物の割り当てによって対応づけられる,多対一のマッチングがあるときに生じる.図6-12の例では,3匹の猫が2匹ずつ魚を持っている.

これは直前の,同等のグルーピングと同じものであるように見えるかもしれない.しかしながら,猫という,配られる対象の存在が,場面の理解を容易にしていることに注意したい.幼い子どもたちには,「2個ずつのキャンディが3つある」よりも「3匹の猫の人形に2個ずつのキャンディをあげる」ほうが,分かりやすい.マッチングの言葉は親しまれており,そして配られる対象の存在が,出現する2つの数のうち一方だけを内面化し影響を与えるものとなっている.)

(pp.159-160)

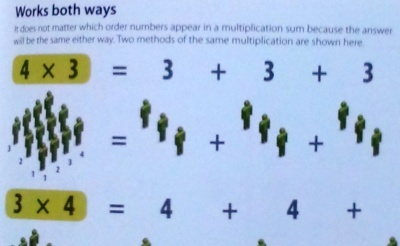

The balance or symmetry in the multiplication square relates to a very important property called the commutative property of multiplication, which states that for any two numbers a and b, a×b=b×a (for example, 3×4=4×3). Note that this is a property of numbers. While it is true that 3×4 is equal to 4×3, 3×4 may not be the same as 4×3 in a real-life situation.

(かけ算の表の釣り合いや対称性は,乗法の交換法則と呼ばれる重要な性質に関連している.すなわち,任意の2つの数aおよびbに対して,a×b=b×aである.例えば3×4=4×3となる.注意しないといけないのは,これは数の性質ということである.3×4が4×3と等しいのは事実だが,日常生活においてそれらが同じであるというわけではない.)

(p.177)

Vergnaud (1988)

- Vergnaud, G. (1988). Multiplicative Structures. In Hiebert, J. and Behr, M. (Eds.), Number Concepts and Operations in the Middle Grades, Vol.2, pp.141-161. isbn:0873532651

1. Connie wants to buy 4 plastic cars. They cost 5 dollars each. How much does she have to pay?

a) 5+5+5+5=20

b) 4・5=20

c) 5・4=20

d) 4+4+4+4+4=20

(1. コニーは4個のおもちゃの車を買いたい.1個は5ドルする.いくら払わないといけないか?

a) 5+5+5+5=20

b) 5×4=20 *1

c) 4×5=20

d) 4+4+4+4+4=20)

(p.144)

5. A rectangular room is 5 meters long and 4 meters wide. What is the area?

m) 4・5=20

n) 5・4=20

(5. 長方形の部屋の長さは5m,幅は4mである.その面積は?

m) 5×4=20

n) 4×5=20)

(p.145)

The comparative facility of isomorphic over functional properties is even easier to show by considering all four procedures a, b, c, and d. Procedure b is a meaningful concatenation of procedure a. The cost of 4 cars = the cost of 1 car, plus the cost of 1 car, plus the cost of 1 car, plus the cost of 1 car. Expressed formally in terms of the isomorphic property for addition, this is f(1+1+1+1) = f(1)+f(1)+f(1)+f(1), and in terms of the isomorphic property for multiplication, f(4・1)=4・f(1). Procedure d is meaningless in terms of cars and costs. Twenty dollars cannot be 5 cars + 5 cars + 5 cars + 5 cars. Young students apparently are aware of this and never user procedure d. So there is a strong asymmetry between procedures b and c. They are not conceptually the same, although because of the commutativity of multiplication they may be mathematically equivalent.

Procedures m and n look very much like procedures b and c, but there is no asymmetry between m and n because the product of length by width is conceptually the same as the product of width by length. The structure it involves is a product of measures rather than a simple proportion.

(同型性は,4つの手続きaからdまでをまとめて検討することで,より容易に示される.手続きbは,手続きaと意味をもってつながっている.4台の値段とは,1台の値段+1台の値段+1台の値段+1台の値段である.加法における同型性を,式で表すと,f(1+1+1+1)=f(1)+f(1)+f(1)+f(1)であり,乗法における同型性によって,f(4・1)=4・f(1)となる.手続きdは,車の数と価格の観点から,無意味である.20ドルは,5台の車+5台の車+5台の車+5台の車にはなり得ない.幼い生徒たちはどうやらそのことに気づいているらしく,決して手続きdを使わない.そのため,手続きbとcの間には強い非対称性がある.それらは,乗法の交換法則によって数学的には等しいかもしれないが,概念的には同一ではない.

手続きmとnは,手続きbとcに非常によく似ているが,mとnの間に非対称性はない.というのも,「長さ×幅」の積は,「幅×長さ」の積と概念的に同一なためである.そこに含まれる構造は,量どうしの積であり,単純な比例ではない.)

(p.146)

Greer (1992)

- Greer, B. (1992). Multiplication and Division as Models of Situations. In Grouws D.A. (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Mathematics Teaching and Learning, National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, pp.276-295. isbn:1593115989

A situation in which there is a number of groups of objects having the same number in each group normally constitutes a child's earliest encounter with an application for multiplication. For example,

3 children have 4 cookies each. How many cookies do they have altogether?

Within this conceptualization, the two numbers play clearly different roles. The number of children is the multiplier that operates on the number of cookies, the multiplicand, to produce the answer. A consequence of this asymmetry is that two types of division may be distinguished.

(いくつかのグループがあって,各グループで同じ個数のモノがあるときというのが,子どもが最初にかけ算を用いる場面になる.例えば3人の子どもが4つずつクッキーを持っている.全部合わせるとクッキーは何個か?

これをかけ算の式で表そうとするとき,2つの数は明らかに異なる役割を担っている.子どもの数は「乗数」であり,クッキーの数すなわち「被乗数」に作用して,答えとなる総数が得られる.この非対称性から言えるのは,2種類のわり算を考えることができてそれぞれ区別されるということである.)

(p.276)

Cartesian products provide a quite different context for multiplication of natural numbers. An example of such a problem is

If 4 boys and 3 girls are dancing, how many different partnerships are possible?

This class of situations corresponds to the formal definition of m × n in terms of the number of distinct ordered pairs that can be formed when the first member of each pair belongs to a set with m elements and the second to a set with n elements. This sophisticated way of defining multiplication of integers was formalized relatively recently in historical terms.

There is a symmetry between the roles of the two numbers here, and hence only one type of division problem. Given that there are 12 possible partnerships, there is no essential difference between (a) being told that there are 4 boys and asked how many girls there are and (b) being told that there are 3 girls and asked how many boys. (In fact, it would be unusual to pose division problems of this type.)

(デカルト積は,自然数の乗法に対してまったく異なる文脈を与える.例題を示す.4人の男の子と3人の女の子がダンスをするとき,男女のペアは何通りできるか?

一般化すると,順序対の総数を求めようということである.その際,各順序対の最初はm個の要素からなる集合に,また2番目はn個の要素からなる集合に属する.そうすると,総数はm×nで表される.このような整数の乗法の定義は,比較的最近になって,歴史的な観点でなされるようになった.

この場合,×の前後に書く2つの数の役割は対称性を持ち,したがって除法の問題は1種類だけとなる.男女のペアは12通りであることを前提として,「(a) 4人の男の子がいるとき,女の子は何人いるか?」と「(b) 3人の女の子がいるとき,男の子は何人いるか?」との間に本質的な違いはない.(とはいえ,こんな形のわり算の問いを出題するのは普通じゃないんだけど.))

(p.277)

- Equal groups

- 3 children each have 4 oranges. How many oranges do they have altogether?

- 12 oranges are shared equally among 3 children. How many does each get?

- If you have 12 oranges, how many children can you give 4 oranges?

- Equal measures

- 3 children have 4.2 liters of orange juice. How much orange juice do they have altogether?

- 12.6 liters of orange juice is shared equally among 3 children. How much does each get?

- If you have 12.6 liters of orange juice, to how many children can you give 4.2 liters?

- Rate

- Measure conversion

- An inch is about 2.54 centimeters. About how long is 3.1 inches in centimeters?

- 3.1 inches is about 7.84 centimeters. About how many centimeters are there in an inch?

- An inch is about 2.54 centimeters. About how long in inches is 7.84 centimeters?

- Multiplicative comparison

- Iron is 0.88 times as heavy as copper. If a piece of copper weights 4.2 kg how much does a piece of iron the same size weigh?

- Iron is 0.88 times as heavy as copper. If a piece of iron weighs 3.7 kg, how much does a piece of copper the same size weigh?

- If equally sized pieces of iron and copper with 3.7 kg and 4.2 kg respectively, how heavy is iron relative to copper?

- Part/whole

- A college passed the top 3/5 of its students in an exam. If 80 students did the exam, how many passed?

- A college passed the top 3/5 of its students in an exam. If 48 passed, how many students sat the exam?

- A college passed the top 48 out of 80 students who sat an exam. What fraction of the students passed?

- Multiplicative change

- A piece of elastic can be stretched to 3.3 times its original length. What is the length of a piece 4.2 meters long when fully stretched?

- A piece of elastic can be stretched to 3.3 times its original length. When fully stretched it is 13.9 meters long. What was its original length?

- A piece of elastic 4.2 meters long can be stretched 13.9 meters. By what factor is it lengthened?

- Cartesian product

- If there are 3 routes from A to B, and 4 routes from B to C, how many different ways are there of going from A to C via B?

- If there are 12 different routes from A to C via B, and 3 routes from A to B, how many routes are there from B to C?

- Rectangular area

- What is the area of a rectangle 3.3 meters long by 4.2 meters wide?

- If the area of a rectangle is 13.9 m2 and the length is 3.3 m what is the width?

- Product of measures

- If a heater uses 3.3 kilowatts of electricity for 4.2 hours, how many kilowatt-hours is that?

- A heater uses 3.3 kilowatts per hours. For how long can it be used on 13.9 kilowatt hour of electricity?

- (同等のグループ

- 3人の子どもが4つずつミカンを持っている.全部合わせると何個になるか?(4×3=12)

- 12個のミカンを,3人の子どもで同じ数になるよう分ける.1人につき何個もらうか?(12÷3=4)

- 12個のミカンがあって,4個ずつ与えていくなら,何人に与えられるか?(12÷4=3)

- 同等の量

- 3人の子どもが4.2リットルずつミカンジュースを持っている.全部合わせると何リットルになるか?(4.2×3=12.6)

- 12.6リットルのミカンジュースを,3人の子どもで同じ量になるよう分ける.1人につき何リットルもらうか?(12.6÷3=4.2)

- 12.6リットルのミカンジュースがあって,4.2リットルずつ与えていくなら,何人に与えられるか?(12.6÷4.2=3)

- 率(変化率,割合)

- ボートが毎秒4.2メートルの決まった速度で進んでいる.3.3秒でどれだけ進むか?(4.2×3.3=13.86)

- ボートが3.3秒で1.39メートル進んだ.平均速度は毎秒何メートルか?(13.9÷3.3=4.2121…)

- 毎秒4.2メートルの速さで,13.9メートルを進むには何秒かかるか?(13.9÷4.2=3.3095…)

- 単位の変換

- 1インチはおよそ2.54センチメートルである.3.1インチはおよそ何センチメートルか?(3.1×2.54=7.874)

- 3.1インチはおよそ7.84センチメートルである.1インチはおよそ何センチメートルか?(7.84÷3.1=2.529…)

- 1インチはおよそ2.54センチメートルである.7.84センチメートルはおよそ何インチか?(7.84÷2.54=3.086…)

- 乗法的な比較*2

- 鉄の重さは銅の0.88倍である.ある銅のかたまりが4.2kgのとき,それと同じ大きさの鉄のかたまりは何kgか?(4.2×0.88=3.696)

- 鉄の重さは銅の0.88倍である.ある鉄のかたまりが3.7kgのとき,それと同じ大きさの銅のかたまりは何kgか?(3.7÷0.88=4.2045…)

- 同じ大きさの鉄のかたまりと銅のかたまりがあって,それぞれの重さが3.7kgと4.2kgのとき,鉄は銅の何倍の重さか?(3.7÷4.2=0.8809…)

- 全体と部分の関係

- ある大学では,試験で上位3/5の学生を合格にした.80人の学生が試験を受けたなら,何人が合格したか?(80×3/5=48)

- ある大学では,試験で上位3/5の学生を合格にした.48人の学生が合格したなら,何人が試験を受けたか?(48÷3/5=80)

- ある大学では,試験を受けた80人の学生のうち上位48人を合格にした.合格者の割合は?(48÷80=3/5)

- 乗法的な変化

- あるゴムバンドは,元の長さの3.3倍まで伸ばすことができる.元の長さが4.2メートルのとき,完全に伸ばしたら何メートルになるか?(4.2×3.3=13.86)

- あるゴムバンドは,元の長さの3.3倍まで伸ばすことができる.完全に伸ばした状態で13.9メートルのとき,元の長さは何メートルか?(13.9÷3.3=4.2121…)

- あるゴムバンドは,4.2メートルから,13.9メートルまで伸ばすことができる.長さは何倍になるか?(13.9÷4.2=3.3095…)

- デカルト積

- AからBへ行くルートが3通りあり,BからCへ行くルートが4通りあるとき,AからBを経由してCへ行くルートは何通りあるか?(3×4=12)

- AからBを経由してCへ行くルートが12通りあって,AからBへ行くルートが3通りあるとき,BからCへ行くルートは何通りあるか?(12÷3=4)

- 長方形の面積

- 縦3.3メートル,横4.2メートルの長方形の面積はいくらか?(3.3×4.2=13.86)

- ある長方形の面積が13.9平方メートルで,縦の長さが3.3メートルのとき,横は何メートルか?(13.9÷3.3=4.2121…)

- 量の積

- ある暖房機が3.3キロワットの電力を4.2時間で消費するとき,電力量はいくらか?(3.3×4.2=13.86)

- ある暖房機は1時間につき3.3キロワットを消費する.13.9キロワット時の電力量を消費するには,どれだけの時間,使用することになるか?(13.9÷3.3=4.2121…))

(p.280, TABLE 13-1. Situations Modelled by Multiplication and Division)

For multiplication, they proposed that the primitive model is repeated addition. In an equal-groups situation, such as 3 children having 4 oranges each, the situation can be conceptualized as 4 oranges + 4 oranges + 4 oranges, and the answer can then be calculated by repeated addition. This representation generalizes naturally to a situation such as 3 children having 4.2 liters of orange juice each, which can be conceptualized as 4.2 liters + 4.2 liters + 4.2 liters. For a situation to be assimilable to this model, the crucial factor is that the multiplier must be an integer; no restriction applies to the multiplicand. Moreover, this model of multiplication carries the implication that the result is always larger than the multiplicand.

For equal groups or equal measures, this condition is met by definition. However, the multiplicand/multiplier distinction applies in other classes of situation (see Table 13.1) and, in general, multiplicand and multiplier may be integers, fractions, or decimals. For example, consider the following contrasting pair:

A rocket travels at a speed of 16 miles per second. How far does it travel in 0.85 seconds?

A rocket travels at a speed of 0.85 miles per second. How far does it travel in 16 seconds?

From a purely computational point of view both problems involve the multiplication of 16 and 0.85, but the former is more difficult to envisage as requiring multiplication for solution; many children, indeed, judge that the answer would be given by 16÷0.85 (Greer, 1988).

Results from several experiments using problems from a variety of situation classes consistently show the multiplier effect (De Corte, Verschaffel, & Van Coillie, 1998, p. 203), namely that the difficulty of recognizing multiplication as the appropriate operation for the solution of a problem depends on whether the multiplier is an integer, a decimal greater than 1, or a decimal less than 1 (Bell et al., 1984; De Corte et al., 1988; Fischbein et al., 1985; Luke, 1988; Mangan, 1986). The size of the effect, in terms of the difference in percentage of correct choices, is of the order of 10-15% for the difference between integer and decimal greater than 1 as multiplier. For the difference between integer and decimal less than 1, the size of the effect is of the order of 40%-50%. When the multiplier is less than 1, there is the added difficulty that the result is smaller than the multiplicand, which is incompatible with the repeated addition model. By contrast, the findings from these experiments show that it makes no appreciable difference what type of number appears as the multiplicand. Thus, these results for the interpretation of word problems modeled by multiplication show a clear pattern that is consistent with the theory advanced by Fischbein et al.

(乗法に対して,彼ら(訳注1)はその原始的なモデルは累加であると述べた.「同等のグループ」の場面,例えば3人の子どもが4個ずつオレンジを持っているというとき,その場面は4+4+4として概念化され,その答え(総数)は累加によって計算できる.この立式の仕方は一般化して,3人の子どもが4.2リットルずつのオレンジジュースを持っているという場面にも適用できる.式は4.2+4.2+4.2と表せる.このモデル(累加モデル)に属する場面の,重要な特徴は,乗数が整数でなければならないことである.被乗数に制約はない.さらに,このモデルでは,結果が常に被乗数よりも大きくなる(訳注2)ことを含んでいる.

「同等のグループ」あるいは「同等の量」に対して,この性質は明らかに満たされる.しかし,被乗数と乗数の区別は(表13.1にある)他の場面の分類にも見られ,そのとき一般に,被乗数と乗数は整数・分数・小数のいずれでもよい.例えば,次の対照的なペアを考えよう:

あるロケットは1秒間に16マイルのスピードで進む.0.85秒ではどれだけ進むか?

あるロケットは1秒間に0.85マイルのスピードで進む.16秒ではどれだけ進むか?

純粋に,計算の観点では,どちらの問題も,16と0.85をかければ答えとなる.しかし前者のほうが,答えとして乗法を使用すると考えるのが難しい.実際,多くの子どもたちが,16÷0.85を解答として選択している(訳注3).

様々な分類の(乗法の)場面に基づいた出題で,実験がなされ,いずれも乗数効果,すなわち,ある問題を解く際に適切な演算として乗法を認識・選択することの困難さが,乗数が「整数」「1より大きい小数」「1より小さい小数」のうちどれであるかに依ること,を示している.効果の大きさを,正答率の差で表すことにすると,乗数が「整数」と「1より大きい小数」の間では10-15%である.乗数が「整数」と「1より小さい小数」の間では,効果の大きさは40-50%になる.乗数が「1より小さい小数」のとき,積が被乗数よりも小さくなる(累加モデルには見られない)ため,難しさがアップしている.その一方で,これらの実験の知見として,被乗数が「整数」「1より大きい小数」「1より小さい小数」のいずれであるかは,感知できるほどの違いを見せていない.乗法の文章題の解釈に関する,この結果は,Fischbeinらが提案した理論に合致し,明確なパターンを示している.)

(p.286)

訳注1:Fischbeinらを指す.この記述の前に,一つ文献が紹介されている.

訳注2:0をかける場合は想定していない.実際,「0人の子どもが4個ずつオレンジを持っている」「0人の子どもが4.2リットルずつのオレンジジュースを持っている」というシチュエーションは変だ.

訳注3:選択肢の中から正しい式を選ばせる出題であるのが前提と思われる.

Shoenfield (2008)

- Shoenfield, A.H. (2008). Research methods in (mathematics) education. In English, L.D. (Ed.), Handbook of International Research in Mathematics Education, Routledge, pp.467-519 (2008). asin:0805858768

10. It is possible to perform calculation such as 384 × 673 mentally by rehearsing the subtotals. For example, one can calculate 3 × 384 = 1152 and repeat "1152" mentally until it becomes a "chunk" which only occupies one short-term memory buffer. "Chunking" is a well-documented mechanism by which people can perform mental tasks.

(p.514)

Yoshida (2009)

- Yoshida, M. (2009). Is Multiplication Just Repeated Addition? ― Insights from Japanese Mathematics Textbooks for Expanding the Multiplication Concept, 2009 NCTM Annual Conference. http://www.globaledresources.com/resources/assets/042309_Multiplication_v2.pdf

- Multiplication sentences describe equal set situations.

- Repeated addition and skip counting are ways to find the total (product).

- The numbers in a multiplication sentences mean something specific:

- Number in a group - multiplicand

- Number of groups - multiplier

- Total number of objects - product

- (かけ算の式は,それと数の等しい,決まった状況を表す.

- 累加や,まとめて数えることは,いずれも総数(積)を求める方法である.

- かけ算の式に現れる数には,明確な意味がある.

- 1つのグループに含まれる数=かけられる数

- グループの数=かける数

- 対象の総数=積)

(p.11)

The Multiplication Table of 5

5×1=5……five, one, 5

5×2=10……five, two, 10

5×3=15……five, three, 15

(5の段

5×1=5……ごいちがご

5×2=10……ごにじゅう

5×3=15……ごさんじゅうご)

(p.12)

If a tape is as long as two 3cm tapes put together, we can say the tape is "2 times" as long as 3cm tape.

You can use the multiplication math sentence 3×2 to fing the length that is two times as long as 3cm.

(あるテープが,3cmのテープ2本をつなげたのと同じ長さなら,それは3cmのテープの「2倍」の長さと言うことができます.

かけ算の式3×2を使って,3cmのテープの2倍の長さを求めることができます.)

(p.17)

Isoda & Olfos (2009)

- Isoda, M. and Olfos, R. (2009). La enseñanza de la multiplicación: el estudio de clases y las demandas curriculares. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA89718362 http://math-info.criced.tsukuba.ac.jp/upload/MultiplicationIsodaOlfos.pdf

Nunokawa (2010)

- Nunokawa, K. (2010). Multiplication: introduction, 日本数学教育学会誌, No.92, Vol.11, pp.122-123. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/110007994852

Students are required to clearly distinguish between multiplicands and multipliers at this stage because this distinction helps them understand the meaning of multiplication. Teachers pay attention to whether their students understand that multiplicands express sizes of units and multipliers express numbers of groups. These meanings are reversed from the viewpoint of some educators elsewhere in the world. The amount of oranges in Figure 1 is expressed as 4×6=24 in Japan. The expression 6×4 is not usually allowed at the introductory stage.

(p.122)

Vorderman (2010)

- Vorderman, C. (2010). Help Your Kids With Maths, Dorling Kindersley. isbn:9781405322461

(最終更新:2013-02-21 早朝)